Saturday, May 31, 2025

Culture Creep: Notes on the Pop Apocalypse by Alice Bolin

Tuesday, May 20, 2025

Aggregated Discontent: Confessions of the Last Normal Woman by Harron Walker

Aggregated Discontent: Confessions of the Last Normal Woman by Harron Walker

Big thanks to Random House Publishing Group and NetGalley

for sending me an advanced copy of Harron Walker’s collection of essays and

articles titled Aggregated Discontent: Confessions of the Last Normal Woman.

This book was not on my radar, but I am so glad I received a digital copy. This

was a thoughtful and intriguing collection of essays and articles, showcasing

Walker’s range as a writer and culture critic. I was not familiar with Harron

Walker’s writing but will keep my eye out for her articles since I found these

articles both humorous and enlightening. I laughed and learned throughout this

book, while also appreciating Walker’s candor and willingness to share about

her experiences as a trans woman since hers is not an experience that I am

familiar with. When I started this book, I thought that maybe Walker was one of

the first trans woman writers, but throughout her book, she frequently cites

other authors, auteurs, activists, and artists who also happen to be trans. Reading

Walker’s essays, for me, was like opening up a curtain to a new range of

experiences for a group that it seems is increasingly marginalized and

stigmatized. Walker makes note of this, but also challenges those perceptions throughout

her essays. I thoroughly appreciated how her work humanizes a group that was mislabeled

as a threat to children during the last presidential election. Although I no

longer live in PA, I’m close enough to Philly to catch many of the radio

stations, and I was shocked to hear that the current PA senator’s pitch to be

elected was fear mongering about the (non) threat of trans athletes, promising

to protect female athletes in PA. One of the last essays in the collection

highlights the increasing number of legislation against people who identify as

trans, and as Walker explains, often pushes them to seek out treatments, medication,

and other care in the black market, which not only puts a vulnerable group like

the Trans community at further risk, but it also possibly creates further

health risks. While Walker documents the more recent legislation, Cynthia Carr’s

amazing biography of Candy Darling (Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar)

noted how her cancer was most likely a result of malpractice with doctors giving

her bad hormone pills.

I really enjoyed all of these articles, but I felt like

Walker is at her best when she is surveying the work of an artist or critiquing

an aspect of society. “Pick Me”, the second essay, is an interesting critique

of the kind of the performative activism seen on social media and more recently

by major corporations. She starts the article by recounting her own experience

working in a store, appreciating the people she encounters, when she is

notified of a new campaign to elevate the voices of Trans employees at a

popular store. This prompts her to visit the stores, wondering how many Trans

workers they actually employ in several of their Manhattan locations.

Furthermore, Walker documents the various statistics and Trans testimonials

that are displayed on LED screens in the storefront window. I usually don’t

think much about these kinds of events, but Walker’s thoughtfulness to dig

deeper and be skeptical of this campaign speaks through her experiences and

challenges with finding and maintaining work as a Trans woman. Many of the

articles focus on Walker’s experiences with work, an area that often is a

challenge for people who identify as Trans. Walker finds that despite the

campaign, there are no Trans workers in any of the 6 stores, although many of

the clerks mention that there may be some corporate employees who identify as

Trans. Her questioning and critique emphasizes that while it is good to raise

awareness of the challenges that Trans people face, they still face barriers to

areas like employment, housing, and appropriate medical care, and this company

seemed to not contribute to making things better. It was also interesting to

consider how the media often reports on Trans issues, framing it almost always

as dire and at-risk. While there disheartening statistics about the disparity that

many Trans people experience, Harron also challenges this notion by presenting other

stories highlighting Trans couples preparing for children and how supportive and

“mothering” the Trans community is.

“Discontent”, the next essay, is a harrowing portrait of

Walker’s work in media, and the challenges she faces navigating a problematic

boss who wasn’t even sure what she wanted. While my work experiences have been

mostly positive, I’ve definitely had some challenging bosses to work for;

however, Harron’s job was providing her with health care that would ultimately

pay for her transition, so her experience navigating the kind of harassment and

disparity in treatment and expectations were downplayed to a certain extent to

pursue her healthcare. This article demonstrated the kind of work challenges

that Trans people face, as well as the difficulties in obtaining the health

care that they need, and the kinds of mistreatment they might endure to obtain

that kind of care. One of my favorite essays was “What’s New and Different?”,

which is a fabulous sequel to The Devil Wears Prada that somehow

synthesizes another Anne Hathaway film The Intern. It is a brilliant and

hilarious creative juxtaposition that manages to also critique the cruelty of

the “Girlboss” and how that kind of punishment of working women is almost like

a generational trauma, passed down from woman to woman. Walker goes on to critique

other 80s films that are predecessors of The Devil Wears Prada—notably Working

Girls and Working Girl (the more popular film). Throughout these

films, Walker highlights the ways that the woman bosses take advantage of and

mistreat their workers, wondering if this kind of treatment (or mistreatment)

in popular media stems from marginalized identities, and not just gender. It’s

an interesting point to consider, and I loved how Walker investigates this through

film, but also creates this speculative sequel

to popular films. It was also interesting to read about Working Girl,

the Lizzie Borden film that preceded Mike Nicols’ Working Girls. I’ve

read about Born in Flames before, and I’m pretty sure I’ve also read something

about Working Girls, but I’ve never seen this film. Walker’s description

and analysis of the film does make me want to track it down.

“Monkey’s Paw Girl Edition” presents a unique dilemma for

Trans women, and again, it was not something I would have ever considered, but

Walker presents her concern about walking down the street, being aware of her

appearance, and encountering a group of men, hoping that they display misogyny

rather identifying her Transness. This leads into the second part about what

being treated like a woman really means, and experience the mistreatment,

misogyny and harassment they experience.

My favorite piece was “She Wants, She Takes, She Pretends”

which was about the artist Greer Lankton, who I am so glad that I found through

Walker’s article. Taking a break during my reading of this piece, I looked up

Lankton’s amazing doll work and other sculptures, and was transfixed—or maybe

just enthralled with the haunting quality of her work. Walker provides both a

biography and an overview of Lankton’s themes and interests in her work, highlighting

some of the ideas. It was incredibly interesting to learn how Lankton

transitioned, and how her parents played a role in supporting her, although

Walker also notes that there might be some ambiguity or uncertainty about the

role her parents played. Regardless, Lankton was able to transition with her

father’s insurance. It seemed like her parents recognized that Lankton was different

from other boys, and as a result, was possibly lonely. She began creating dolls,

possibly as a way to keep her company, but also as a reflection of herself. One

of the other interesting parts about this article was Walker noting Lankton had

many photobooth pictures of her transitioning, which it sounded like was

something Walker also did to document her own transition. Maybe the dolls were

also a way for her to further alter her image or to further present the possibilities

of her identity and presenting herself to the world. Regardless, I was fascinated

with her work and couldn’t believe I hadn’t heard of her before.

Another favorite was “A Trans Panic, So to Speak,” which

examined Ed Wood’s Glen or Glenda, described as possibly “an

unexpectedly earnest plea for acceptance”, but it also seems to castigate transsexuals

with the Alan/Ann subplot. As Walker explains, both stories have paths to

acceptance, where Glen is social, Ann’s is medical, with hormones and surgery. I

didn’t realize that there were these attempts to draw “some distance between

themselves and other sexual deviants. Rather than trying to find common ground

with all the homosexuals, transsexuals, and drag queens…” This article not only

takes a unique approach to analyzing a classic Z movie, but also finds a way to

examine how these attempts at representation and normalizing ended up further

stigmatizing marginalized groups like the Trans community. Walker also brings

in her own experience with her date, and questioning his own gender identity, possibly

due to his “ethical non-monogamy”, which I wasn’t even aware was a thing.

Again, I felt like I learned so much from this book. The last few articles, “Sterility”,

“Fertility”, and In/fertility” all dealt with further barriers and complications

Trans men and women face, but Walker also ties in her own experiences as well

as those of friends and prominent Trans activists and artists. These were also some

excellent chapters that all touched on topics related to family, relationships,

and health. There were great points to consider, especially about the idea of

family and what it means to people who identify as Trans. Walker explains how

the Trans community has becoming mothering, and how many older Trans members

end up taking on roles where they mother the younger generation who may have

been turned out by family and face barriers to housing and jobs. Walker not

only examines this supportive community, but is also turning her critical eye

back to these barriers and access to care and basic necessities of survival,

and how members of the Trans community are often more at risk due to their

marginalized status in society. We see this even more within the past few

months of the new/old administration that continues its assault on non-normative

groups. If anything, Walker’s book is coming out at the perfect time to confront

the disinformation and biases. Although I’m not sure whether anyone in the

White House reads at all, I can see these essays being valuable in the kinds of

anthologies used in first year writing courses. Walker’s perspective brings an

important but often under-represented eye to important issues that most young

people will experience either in college or after graduation. Plus, her work is

funny and humanizing; that is, it shows us how Trans people live, laugh, and

love, while also raising awareness about the barriers and issues with accessibility

they often face. I really hope that instructors and curriculum developers

consider incorporating any of these essays into their courses. Highly

recommended collection!

Friday, May 16, 2025

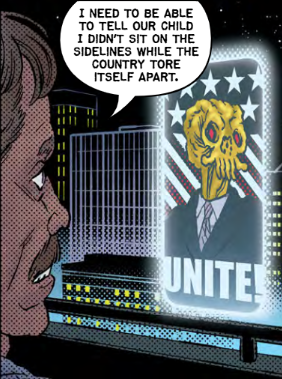

More EC Horrors: EC Cruel Universe Vol. 1

EC Cruel Universe Vol. 1

Big thanks to Oni Press and NetGalley for providing me with

an advanced copy of their second EC relaunch Cruel Universe Vol. 1. I

read a version in the NetGalley reader, and was primarily reading them on my iPad,

which provided a great viewing experience, since I was able to see larger

panels in vibrant color. I am really enjoying these reboots. Although sometimes

I feel like these reboots and updated versions lack creativity or imagination,

I think the stories in both EC Collections (Epitaphs from the Abyss is

the horror themed, Tales from the Crypt version) are unique and present some

modern takes on horror and technology, while also maintaining the ironic twists

of fate that are a part of the original EC comics. While the Epitaphs from the Abyss was more of a horror themed set of stories, this collection was

focused on science fiction and a kind of dystopia. I initially thought this would

be strictly sci-fi, but there are stories that are horror themed and also

feature the kind of cosmic horror that is in the vein of H.P. Lovecraft. Throughout

all the stories, the artwork is great. I noticed in a few stories, there are

some common themes in some of the outcomes to individuals in the stories, and I

was surprised at the level of gore for a sci-fi collection. However, as the

title indicates, these tales are part of a Cruel Universe, where people

are subject to violence and brutality, as well as the whims of fate. In really

enjoyed the space themed stories and those with aliens. I thought the artwork

for these stories was particularly striking and original. Many of the aliens

captured the kind of Lovecraftian image of Cthulhu, with tentacles and octopus-like

appearances. One of the earliest stories, “Solo Shift”, features an interesting

image of a black hole with really great colors. I also liked the kind of socio-economic

themes that ran throughout stories like “Priceless” , “Organic”, “And the

Profit Said…”, and “Paring Knife”, which all deal with people on the fringes of

society or who are subject to a lower social ranking than others. In these

stories, there is some kind of ironic twist at the end where we see how those

with power maybe are not as powerful as they once seemed or their arrogance

brings about a downfall, akin to hamartia in Greek tragedy. Other stories tell

of the dark side of technology, and some are particularly relevant today. “Drink

Up” was a unique and short tale about a rich man’s quest for immortality, as was

“Billionaire Trust”, which had a particularly interesting ending. “Automated”

was the story of a tech titan and car designer who brings about the destruction

of society with his overreliance on automation (sound familiar?). I also really

enjoyed “The Deleted Man”, which shows the lengths that people may go to in

order to have their online histories “altered”. Two other favorites were “We

Drown on Earth” and “The Ink Spot Test” for their creativity and illustrations.

“We Drown on Earth” was especially Lovecraftian, but also focuses on the kinds

of risks and problems that corporations exert on their workers. The creatures

in the story are particularly creepy and well-drawn. I loved the background art

in “The Ink Spot Test”, and the story is somewhat similar to a book I just

finished on MKULTRA. I also really enjoyed the covers presented at the back of

the book. There were some awesome illustrations there as well.

Overall, this was a great collection. I really enjoyed these

stories, and most of them were great with unique and innovative twists and

timely stories that are relevant to our current climate, and yet still maintain

an element of that classic EC twist of fate. Highly recommended!

America's Hidden History of Mind Control: Project Mind Control: Sidney Gottlieb, the CIA, and the Tragedy of MKULTRA by John Lisle

Project Mind Control: Sidney Gottlieb, the CIA, and the Tragedy of MKULTRA by John Lisle

Major thanks to St. Martin’s Press and NetGalley for

providing me with an advanced copy of John Lisle’s deeply researched book about

a horrible hidden history in America’s intelligence agency Project Mind Control: Sidney Gottlieb, the CIA, and the Tragedy of MKULTRA. I am

fascinated by this period not only because it was classified for many years,

but also because it is so shocking that the American government would allow

indiscriminate human testing with drugs and other forms of psychological

torture even after the Belmont Report. However, I think that Lisle recognizes

how this kind of thinking and action are part of the continuous pendulum that

swings back and forth across American history. He states this argument well in one of the

last chapters that provides a kind of analysis and evaluation of MKULTRA and its

impact on later clandestine actions of intelligence agencies like the CIA and NSA:

“As the previous examples show,

MKULTRA was not a fluke. Rather, it was the norm in a system that lacks

meaningful external oversight and lets perpetrators of abuses avoid

accountability for their actions, a system in which the vicious cycle of

secrecy pushes the pendulum too far toward security at the expense of liberty.”

I really appreciated this insight, and I think it is

something that is lacking in other books about MKULTRA and Gottlieb. I’ve read

a few books about this topic, and Chaos by Tom O’Neill and Poisoner in Chief by Stephen Kinzer both explore similar grounds, yet also delved

into specific areas, with Kinzer’s book providing an overview of Gottlieb’s

career and various projects in the CIA. What separates Lisle’s book is the

deposition transcripts that were used as much of the basis for each of the

chapters. These provide some important insight into the various projects that

Gottlieb was involved in, and also serve as launching points for Lisle to

explore these projects and the individuals who were affected by them. At first,

it was a little jarring to read through these transcripts and I wished that Lesle

provided some insight into the organization of the book; however, about ¼ of

the way through the book, I got used to this approach and actually appreciated

how these transcripts helped to inform the other parts of the chapter.

Furthermore, they also allowed Lisle to take a broader approach than Kinzer or

O’Neill and examine many of the sub-projects that were included under the

MKULTRA program. Readers also learn how the project initially developed in

response to the belief that prisoners of war taken by North Korea and individuals

in other Communist countries (especial Cardinal Mindszenty from Hungary) experienced

a kind of through reform (or informally known as brainwashing). Not really

aware that this kind of shift could be the result of coercive physical punishment

like torture, the American government enlisted scientists and psychologists to explore

the various questions related to mind control, wondering if it were possible to

not only alter one’s belief system and values, but also to possibly alter their

behavior. As Lisle notes in the final chapters and epilogue, this secretive collaboration

between intelligence agencies, psychologists, especially behaviorists, and

scientists was also what we later found out about in the war on terror and the

1980s war on Communism that brought about the Iran Contra Scandal. As Lisle notes,

it’s this kind of fear of other ideologies that ends up deferring power to intelligence, which leads

to secrecy, which invites further abuse. It’s a common thread we see in the fight

against Communism, the fight against terrorism, and even now with the “belief”

that America is under attack by immigrants, although it seems like the abuses are

much more blatant, telegraphed and promoted online to send a message. One of

the other interesting conclusions that Lisle draws in regards to programs like

MKULTRA is the role of that conspiracy theories play in furthering these

abuses. Lisle shows how the CIA has not really addressed this scandal, and the

fact that Gottlieb and others destroyed the files leads to an absence of

evidence. “All claims need some empirical support to have any credibility. Yet

in the twisted world of conspiracy theories, an absence of evidence is itself

evidence of a cover-up. Nothing is proven, nothing can be disproven.” Lisle

explains that many have gone on to use these kinds of absences to connect dots

and create their own theories and beliefs for various outcomes and events. One

example is school shootings and the belief that these are used as a pretext to

remove guns from people. Another is the various reasons for COVID closures and

how this is a scheme by the “deep state” to engage in various actions that will

take away liberty. Lisle goes on to write “Like McCarthyism during the Red

Scare, these sensational claims generate fear, which generates coverage, which

generates converts. Ironically, the conspiracy theorists have managed to

manipulate more people than MKULTRA ever did,” providing an interesting current

analogy to what is happening now with all of the disinformation and “flooding

the zone” to not only manipulate people, but also as a means to call to action,

using fear as a primal motivator. I really appreciated this insight and

analysis that Lisle provides to link up that idea about how behaviorist

techniques are often employed in our current political climate. Lisle also

makes a note about how the political landscape in America also further allows

this kind of approach where there is limited governance and more focus on

appealing to emotion- winning the minds through the hearts—and how this also

contributes to the limited oversight in intelligence abuse. It’s an interesting

idea and throughline that I don’t recall was in some of these other books (or

documentaries like Wormwood and Chaos, based on the O’Neill

book).

Lisle reviews some of the other cases that were in Kinzer’s

book, notably the Frank Olson tragedy (which was the basis for the Wormwood documentary

series). Lisle also explores the roles that other agents and psychiatrists

played in MKULTRA’s research. In particular, there is time spent on the abuse

perpetrated by George White in Operation Midnight Climax, where he used safe

houses in San Francisco and New York to drug people on the fringes of society. The

unwitting drugging of these people was due to the belief that they were less

likely to report the abuses or even question the drugging. Lisle also shares

the attempted follow up that happened after President Ford’s inquiry into CIA misdeeds,

and it was sad to see how these single drugging may have induced paranoia and

mental illness in some of the victims. Similarly, Lisle also highlights the

abuses perpetrated by Dr. Ewen Cameron, a Canadian psychologist whose

experiments in mind control were horrific. Kinzer also explored Cameron’s

abuses in Poisoner in Chief, and Cameron was also the subject of CBC

podcast. However, Lisle focuses more on the patients and what they endured, and

also follows up on some of their lives and the consequences of Cameron’s abuse.

One of his most notorious attempts to erase and reprogram individuals was

through a process called “psychic driving” where patients were forced to listen

to tape loops, often words or phrases they despised or were upsetting to them,

while in a continued drug-induced state for weeks at a time. As Lisle notes,

many times the effects were catastrophic, reducing adult subjects to infant

like states where they were unable to care for themselves. In the end of the

book, Lisle also follows a lawyer for some of these victims, Joseph Raugh, who sought

compensation from the US and the Canadian governments for these wrongdoings.

This examination of the pursuit of justice was also interesting to see, as

Lisle documents the challenges that Raugh experienced in attempting to challenge

the secretive agencies involved in these abuses.

I really enjoyed learning more about this topic through

Lisle’s research and reporting. At first, I was a little concerned that this

was going to be similar to Kinzer’s book, but Lisle approach is to go for more

breadth while also taking some more depth with those projects and people who

were involved in the peripheries of MKULTRA. Furthermore, I thought that the

final chapters that detail the consequences of MKULTRA in fueling further

conspiracies as well as other clandestine programs enacted under the guise of

protecting and securing America were some of the strongest in the book. It was

an apt and timely conclusion to draw as we continue to witness daily attempts

at a form of mind control through disinformation (or censorship through noise),

conspiracy theories, and the kind of methodologies employed by cults to manipulate

and modify behavior (The BITE method-Behavior, Information, Thought, and

Emotion). This section was especially important in becoming a more critical

consumer of information, whether it is through the media, online, or in print.

I’m glad that Lisle’s book adds some additional insight and ideas into the

discussion about MKULTRA and the history of these kinds of clandestine

operations in America. Furthermore, Lisle’s analysis presents important

messages for the current climate of information, both real and fabricated, why

it is important to be critical when consuming information. Highly recommended

book!

Tuesday, May 13, 2025

Things in Nature Merely Grow by Yiyun Li

Things in Nature Merely Grow by Yiyun Li

Many thanks to Farrar, Straus, and Giroux and NetGalley for allowing

me to read an advanced copy of Yiyun Li’s profound new book Things in Nature Merely Grow. Li is one of my favorite writers. I’ve mostly read her short

stories and novels, but I ended up reading Where Reasons End about 2

years ago. That book, as she describes it in Things in Nature Merely Grow,

was dedicated to her son Vincent, who died by suicide 8 years ago at the age of

17. It’s hard to categorize the book since it blurs so many lines as Li extends

conversations, arguments, and questions she discussed with her son, Vincent. In

some ways, it seems to capture his essence, but in others, it allows her to

continue to speak with him, through her writing. It’s beautiful, haunting, and

like Li’s other writing, incredibly moving. I can’t remember if Li explained

the meaning of the title, but it seemed to suggest that keeping that connection

with Vincent is more important than finding reasons why he decided to take his

life. It also suggests that her continued conversations and questions with Vincent

occur outside of logic and reason, and that both to accept his absence and

continue to remain connected work outside of logic. Li’s latest book, Things in Nature Merely Grow, also examines the loss of her other son, James, who

was Vincent’s younger brother. James also decided to take his own life, and

while Li discusses both sons in this book, she also doesn’t dedicate the book

to James, noting that it wouldn’t have been what he wanted and a book wouldn’t

necessarily be able to capture James’ essence the same way her earlier book attempted

to capture Vincent’s essence. Li’s book transcends boundaries of classification

and operates in its own place, both celebrating the individuality of her two

sons and acknowledging their absences due to suicide. Where Vincent was verbose

and at times argumentative, James was contemplative and quiet, often speaking

with a slight smile, which for Li was filled with possible interpretations,

sometimes in opposition to each other.

Li also explains that while Vincent lived a life of emotion,

James lived a life of logic and reason. As a result, Li seems to take a step

back from the loss of both children and examine the facts. I found this approach

to loss unparalleled. I can’t imagine what I would do in this situation, but Li’s

ability to identify the facts and state them provides a way to work towards the

radical acceptance she describes as helping her process her son’s death. I’m

even struggling with the words to describe this, as Li also mentions other’s

challenges with attempts to console her. Sometimes people reveal their true

intentions, and this was some of the most shocking parts of the book. People

asking for editorial help, people possibly using her employment at Princeton as

an in for their children; it was truly shocking. Nevertheless, Li’s radical

acceptance also seems to help her navigate the difficulties and drains of interacting

with people after a loss. Also as a writer and astute observer of people, Li

seems to be an empath and can seem to intuit others’ feelings. I’m not sure if

I would have been able to be as composed as her.

In addition to navigating other people, Li also spends time

reminiscing about the challenge of parenting. I found her memories of taking

care of her sons while she was finishing up her MFA at Iowa’s Writer’s Workshop

also amazing. She mentioned how much of child care in the early years is both

intuitive and reactive. “One does not master the skills of taking care of a

baby by reading a manual or taking a few classes. One fumbles and blunders,

never certain if one has done everything right. One weeps from exhaustion or

frustration, and one worries and loses sleep over anything, small or large.” An

outcome of this kind of reaction and attempts at appeasing this helpless, tiny

human are frustration, exhaustion, and many times fear and anxiety as well. I

was amazed to learn that Li brought James as an infant to class with her, and

continued to teach a week after giving birth. I was also in graduate school

when my son was born, and I remember how hard it was to find the time to teach

and grade after putting him to bed, hoping that he would just sleep through the

night. These moments in the book when Li reflects on her sons’ lives and her

care and nurturing of both of them in different ways were some of the best

parts of the book. It’s both touching and also imbued, for me, with a sense of longing

in the sense of the Portuguese word saudade, which doesn’t really

translate into English. I remember after my dad died, someone mentioned this

word to me, explaining that it was a word that widows of sailors lost at sea

often used. It’s that feeling of loss and nostalgia, with a lack of

understanding or full knowledge of the whereabouts of the person who was lost. Again,

Li doesn’t mention this word, and also doesn’t seem to wish for things to be

different, and therefore, the memories are beautiful ways to communicate the

qualities and differences of her sons, not necessarily to feel nostalgic. If

anything, as I was reading these detailed glimpses of their childhoods, I could

relate to similar memories of behaviors, predilections, or mannerisms that

seemed to communicate more about our own hopes and beliefs, and possibly our

anxieties, about our children’s futures. Li’s observations and recollections

are detailed, nuanced, and subtle, capturing a quick conversation or response

from her sons, observing how they eat different foods at a café after a weekend

activity, as well as the books they encountered and how these texts influenced

their lives. As a result, reader can witness the sense of care and wonder Li

demonstrates for her sons, noting and appreciating their differences and

providing them with the space and support they needed to develop into authentic

selves. Li contrasts these memories with her own experiences growing up in

China, trained to be a mathematician, but secretly seeking to memorize ancient

poems. She details some of the harshness that she experienced when she

attempted to be her authentic self or express her own unique ideas in a society

and culture that seemed to value conformity and accepting the norms over

challenging them with one’s individuality. She shared some of these memories

with her sons, and in one memory, explained that as a special guest in James’ 2nd

grade class, she shocked his classmates because she said that she didn’t like

candy as a child. The story behind her distaste for candy is shocking, but it pales

in comparison to the cruelty inflicted by her mother, who claims that Yiyun was

the daughter she loved most. Li’s mother’s love can only be expressed through

demands, control, and domination. In another story recalling her childhood, Li describes

one of her mother’s methods to elicit compliance (and possibly guilt or shame)

was to claim that Yiyun had a twin with whom her mother preferred to spend time,

since this daughter was the exact opposite of Yiyun. Li’s mother would lock

Yiyun in a room while her mother and sister would pretend to converse and laugh

with Yiyun’s twin. Even more heartbreaking is the way Li describes her reaction

to this kind of cruelty. I can understand how growing up in this kind of

environment would lead someone to the kind of radical acceptance Li acknowledges

was necessary in dealing with the loss of her sons. I can see how the kind of

absurdity in facing violence and scorn as a child would require a kind of

process of analysis and reflection to try to make sense of these events. It’s

not my place to evaluate whether they are right or wrong or what kind of

influence this had on Li. If anything, it seems to have made her more sensitive

and considerate in how she raised her sons, valuing their qualities and nourishing

their interests and passions.

Li uses the metaphor of gardening to also move towards

radical acceptance, and this metaphor is also where the title comes from. In

nature, plants and flowers grow and die. There are other factors that often

make their growth more challenging- animals, weeds, weather, and while we can

tend to gardens and try to cultivate conditions that allow our plants to

thrive, we cannot control everything about nature. We cannot have continuous

growth throughout the year. Plants die off in the fall and winter, only to grow

again in the spring. Li acknowledges that while weeding and creating deterrents

for animals may be important, she also cannot remain angry or upset at their

nature. I appreciated this metaphor for parenting.

We are always trying to cultivate the best environment and opportunities for

our children to grow. However, we cannot control everything. And while it is in

our nature to grow, it is also in our nature to die. It is a sad reality, but a

fact nonetheless, and a fact that accepting may relieve us of some anger or anxiety.

Li also explains that she doesn’t see grief as a process with an endpoint. It is

something that will be her with always, just as she continues to view herself

as a mother of two sons. I agree with Li’s explanation of grief; while my

situation is nowhere near Li’s, even though my father has been dead for some

time, there’s still a kind of hole or emptiness. While this hole was much

greater in the time right after he died, it’s gradually reduced in size over

the subsequent years. Yet, there’s always going to be reminders about his

absences. My kids have never met him, and they always have questions about him.

My wife never met him either, and she’s asked how they might get along. I

wonder how he would view my home, what advice he might give, what he would

think about the world right now. It’s not something that makes me sad or

nostalgic, but just something that is there- a slight opening or void that is a

part of me. For me, Li’s explanation of grief of having no terminal point is

relevant in this regard. I also appreciated the book from this perspective. It’s

not like a manual explaining what to do or how to act in the event of loss, but

Li explains how she continued to engage in her regular activities right after James’

death. She mentions going to a piano lesson in the week after James’ death, and

talking with her teacher, and struggling with learning the pieces, but seeming

to do well with a strange collection of piano exercises from Hanon that a

friend described as “demented”. She doesn’t mention that these pieces relieved

her or brought her joy, but rather it was something to do, something she could

focus on to occupy her. In another section, she presents some practices she

felt were important, and these included things like hydration, exercise, and getting

up at a regular time. When my dad was in the hospital dying, I felt a similar

kind of way, and it is actually how I started running. I just had all this

nervous energy, and I felt like I couldn’t be at the hospital until I ran a few

miles before hand, burning off some of the energy, but also making me more

willing to accept how close death was to me. I also realized that I didn’t want

to just sit around and ruminate, and that I needed to keep busy and occupy

myself. I remember not really crying until a few weeks after his funeral, when

it finally hit me. It’s definitely important to experience that kind of

emotion, but at the same time, Li also mentions not allowing herself the time

to ruminate in bed. I really appreciated this insights for helping someone navigate

this unimaginable loss.

Finally, the other part of the book that stood out to me was

how reading and writing factored into Li’s days after James’ death. She has

mentioned reading Tolstoy in Where Reasons End, but in this book she mentioned

several other works she frequently turned to after James’ death. Li references

Greek and Shakespeare’s tragedies, but also noting that “Those ancient Greeks

sing their grief at the highest pitch, which, as Carson pointed out, is rage.

Their grief and their rage are nearly untranslatable, as though feelings in

extremity can only be physical sensations— the language assails the readers with

a blind and blunt force.” As she further explains, she didn’t necessarily lose

her words, but they said something she had not and expressed their grief in

another, more violent manner. While sometimes literature may present this kind

of grief as a madness, Li’s reference to Constance’s grief in King John

shows that our outward signs of grief can often be misconstrued, especially

when the vocabulary of grief is so ill-defined by others. I really appreciated

Li’s literary references to grief and loss throughout the book, as they help us

understand how others may process grief. Not everyone may seek comfort in words

(words, words, words), but reading and writing allow us not to ruminate. It’s

interesting also since I recently read Sarah Chihaya’s brave memoir Bibliophobia

about how books and reading can be both an experience in joy and exploration

but also can bring terror and depression. Chihaya cites one of Li’s other books

about Li’s own experience with depression and her suicide attempts. I haven’t

read that book yet. I’ve almost been a little intimidated to engage with it.

Yet, for Li, books, works of literature, plays, music, and other forms of art

can be part of the process leading to radical acceptance. Recognizing that we

aren’t alone in this, and being able to approach the facts of the situation and

not impose our own reasons or blame for the events may help in this process. I’ll

have to go back through this book to look at the reading list. While I may not

want to read all of these works, it’s always good to receive recommendations. I’ll

also have to revisit this book at other times; it’s such a beautiful book filled

with touching moments, but also an awareness that things in nature grow. It’s

not a manual, but it’s also not quite a memoir. It’s almost like meditations,

where Li is able to deeply reflect on her sons’ lives and deaths. I’m very

grateful for her willingness to be so honest and reflective, so thoughtful and

considerate when the world may not always be the same.

Saturday, May 10, 2025

Questions about Creativity, Commerce, Corporations in Ling Ling Huang's Immaculate Conception

Immaculate Conception by Ling Ling Huang

Thursday, May 8, 2025

A Unique Twist on Haunted Houses: The Manor of Dreams by Christina Li

The Manor of Dreams by Christina Li

Thanks to Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster and

NetGalley for providing me with an advanced copy of Christina Li’s exciting and

intriguing new novel The Manor of Dreams. I enjoyed this book for its

genre bending story and plot twists, as well as tracking how the characters

have changed and what events affected them throughout their lifetimes in the

alternating timelines between past and present. Furthermore, Li has some lucid

and haunting descriptions of the atmosphere, landscape, and decay for the

setting of this novel in a renovated family mansion that has fallen into

disrepair once again. While this supernatural mystery might not be for

everyone, I thought that Li’s writing, plot twists, and characters created a

compelling and engaging world that kept me reading during the second half of

the book. I also loved the play on words with the title, how it might refer to

a dream house, but it is also about the nature of our dreams and what they

mean. Vivian Yin, one of the main characters, experiences strange, haunting

visions once she moves into Yin Manor, the house of her husband’s family that

he has renovated for both of them. Other characters also experience similar

strange visions, tremors in the middle of the night, and plants that seem to

want to consume people.

The Manor of Dreams starts with the recent death of

one of its main characters, Vivian Yin, the first Chinese actress to win an

Academy Award. Her surviving daughters, Rennie and Lucy and Madeline, Lucy’s

daughter, arrive at the house to review the will and sort through their Ma’s

items. However, they were unaware that the daughter of her mother’s housekeeper

and gardener, Elaine Deng, would be in attendance with her daughter Nora. “Part

One: Root” establishes an incredible amount of tension between these two groups

of women, the Yins and the Dengs. Lucy and Rennie have not seen Elaine for some

time, and based on the tension and Elaine’s rule that Nora should not speak to

the Yins, Li has established that there is some bad feelings and resentment

between these two families. To add to the tension, Lucy and Rennie are

surprised to learn that their mother only had about $20,000 to leave them as an

inheritance, and Vivian left the house to Elaine. This surprise gift, along

with learning that Vivian changed her will about one week prior to her death

adds to Lucy’s suspicion that Elaine had something to do with Vivian’s death.

Lucy begins to investigate, while Elaine digs in and claims the house as her

rightful inheritance, although she does allow Lucy, Madeline, and Rennie to

stay in the house and sort through Vivian’s things for the week. Lucy really

wants to search around for evidence of Elaine’s involvement in the will change

and Vivian’s death. This section also establishes some of the traits of these

characters as we learn that both Lucy and Rennie lived privileged lives,

attending boarding schools. Lucy became a lawyer, while Rennie pursued acting

and modeling. Neither was particularly close with Vivian in her last years, as

Vivian seemed to become a recluse, rarely going out and even firing home help

aides that Lucy hired. We also learn that Elaine was in a PhD program, but

eventually left since it was not a career for her and Nora was about to be

born. Both daughters, Madeline and Nora, are right around the same age, yet have

had different experiences that bring them to this strange encounter over a contested

house. Furthermore, both daughters receive warnings to keep out of the garden,

yet both are somehow drawn there, with Madeline eventually ending up there.

This garden appears strange, and offers some of Li’s most atmospheric and

interesting descriptions: “She leaned in, expecting the buds to have a faint,

sweet scent. But instead the petals emitted that raw, sharp odor of rust.” Flowers,

especially these kinds of strange, decaying and rotting varieties, feature

prominently throughout the book, and not only contribute to the atmospheric mood

of the book, but also represent the kind of decay and rot that is apparent throughout

the house as well. Li’s writing and descriptions of the various decay around the

house contribute to the feeling that death and decay are all around, and this

kind of rotten decay is gradually overtaking the living, having some kind of

impact on their behavior, their well-being, and their interactions with one another.

I loved the way that Li includes this kind of symbolism throughout the book,

and how the decay permeates throughout the plot. This section ends with Madeline

somehow being engulfed by the plant and Nora coming to her rescue, tending to the

wounds that the plant inflicted. I read The Ruins by Scott Smith last

summer, and Li’s The Manor of Dreams might come in second to having some

of the creepiest plants in a book.

“Part Two: Bloom” begins to examine the past to learn more

about how Vivian Yin met her husband, the actor Richard Lowell, and how Vivian

eventually broke into acting and attained acclaim and an Academy Award. These

chapters alternate between the 70s, 80s, 90s, and the present. I also enjoyed

the structure of the book, how readers are confronted with this mystery of why

Vivian didn’t leave the house to her daughters, but rather to the daughter of her

gardener and housekeeper with whom she seemingly had no contact for decades.

These chapters gradually reveal what happened, helping readers understand not

only Vivian’s background, but also those of Elaine and her younger sister

Sophie. We not only learn more about Vivian’s experiences and struggles as a

single mother and aspiring actress in 1970s California, but we also see the

challenges she faces as a person of color and how limited roles were for her in

films. Richard, on the other hand, seems to be a coveted actor who winds

acclaim and seems to easily take on roles in popular and acclaimed movies.

Nevertheless, the couple has a kind of competitive spirit between them that

pushes them to excel in acting and to seek out other opportunities in

filmmaking. Furthermore, Richard is interested in renovating his mother’s

childhood home, which the family sold years ago. His fixation on the past and

desire to recreate the past glory of his family in his own image bring about

challenges, as he and Vivian experience a long period of fixing up the house,

that almost never seems to end. Furthermore, when they move in, there are strange

occurrences like tremors that only Richard feels, burst pipes, and hallucinations

that Vivian witnesses. Vivian learns more about Richard’s family, although she learns

through local library research since Richard doesn’t seem to want to discuss his

family’s background. I found this a little odd, not only with Richard, but with

so many of the characters in the book. While Richard especially seemed

interested in rehabbing his family manor and reshaping it into his own vision,

he didn’t really want to talk about his family history. Lucy, Rennie, and

Elaine also don’t like to discuss their pasts with their daughters, and it

seemed strange that they were all willing to meet up in this decrepit house and

fight over its ownership, despite not really acknowledging the painful pasts

that they share. However, I think that this is part of the message in the book-

that there are consequences for failing to acknowledge one’s past, and that

sometimes, failing to acknowledge the past can create a kind of haunting experience.

I won’t provide any additional plot details because there

are many twists and unexpected turns throughout the book. Furthermore, Li’s parallel

narratives that move between the present and the past help to unravel the

mystery of why Vivian was leaving the home to Elaine and not her daughters.

Initially, we are only left with Vivian’s final words to her lawyer, Reid

Lyman, that leaving the home to her daughters would “ruin them.” As we move

through Vivian’s past, her relationship and marriage to Richard, and the

challenges she faced in Hollywood as an actor of color trying to find parts, we

learn more about the steps she’s taken to protect her daughters and ensure they

have the best in their lives. We also see that Richard’s family, including his

mother, whose microaggressions towards her new daughter-in-law, distance

themselves from the house, leaving readers to wonder whether the house itself

is cursed, or whether there are other factors that may affect inhabitants of

the house. I appreciated the ambiguity and mystery in this story, and Li’s gradual

reveal of the backstory presents some intriguing events and twists. However, Li’s

descriptions of the house, gardens, and flowers were especially evocative and effective

in conveying the sense of decay and decadence within the home. This was the

section that I couldn’t put down, and the short chapters that offered

alternating perspectives of the different characters and their histories kept

me engaged in the story. There is a final part of the book, “Rot”, that jumps

back to the present and provides a climatic end to the story. Again, I don’t

want to spoil this book since I hope that others will read it. Nevertheless, I

really enjoyed this book. It wasn’t exactly what I expected. Although it is

mysterious, I appreciated Li’s use of a kind of gothic horror throughout. Li

presents a unique portrayal of the haunted house story, and leaves readers

wondering about the nature of deceit, evil, and violence in relationships.

Furthermore, it was interesting to note that these aren’t just romantic

relationships, but we also see family relationships, and how withholding

information and past events can impact our relationships with parents and

siblings. Li’s symbolic use of decay throughout, whether in the house, plants,

or even the hallucinations that some characters experience, also help to create

the mysterious and eerie atmosphere of the book. I also appreciated how Li

included Chinese language- characters and words- throughout the book to

emphasize Vivian’s heritage and how she worked to maintain her culture in an

industry and city that tended to stereotype her. It’s not something that I

mentioned throughout this review, but it is another important part of the book.

This is an exciting and engaging read. Highly recommended!